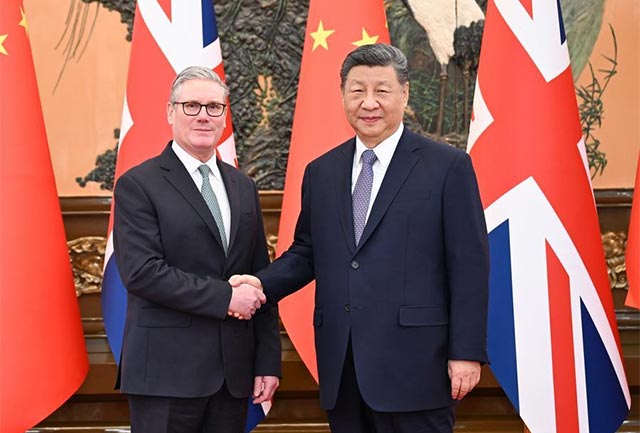

After Carney, Now Starmer: Western leaders adjust in a fragmented world / Photo: Xinhua/Li Xiang

After Carney, Now Starmer: Western leaders adjust in a fragmented world

Tashkent, Uzbekistan (UzDaily.com) — In recent months, Washington’s foreign policy posture has grown increasingly assertive, from its handling of Venezuela’s political crisis to renewed rhetoric about taking control of Greenland. Across the Atlantic, transatlantic unity has shown visible cracks, with disagreements between the United States and the European Union resurfacing over trade, industrial policy, and strategic autonomy. The common thread has been a more transactional and unilateral approach, one that leaves even close partners navigating heightened uncertainty.

Against this backdrop, the timing of British Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s arrival in Beijing is telling. His visit comes less than two weeks after Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney concluded his own trip to China, and follows a broader pattern of European leaders re-engaging with Beijing, including French President Emmanuel Macron and leaders of Ireland and Finland. In London, commentators from the Financial Times to the BBC highlighted the parallel, suggesting that Starmer may have lessons to draw from Carney’s pragmatic recalibration — how middle powers preserve flexibility amid unpredictable external pressures.

It is the first visit by a British prime minister to China in eight years, yet it is not a return to the past. Starmer has emphasized a “sophisticated ” relationship — one that acknowledges differences, manages competition, and maintains channels for cooperation where interests align. Disagreements remain, but dialogue itself is now a strategic asset in a world where reliance on any single partner no longer guarantees economic security.

Economic considerations were central to Starmer’s messaging. Speaking at Beijing’s Forbidden City, he framed deeper engagement with China in terms of domestic priorities: easing the cost-of-living burden, supporting British businesses, creating jobs, and stabilizing supply chains. Accompanied by a sizeable business delegation, Starmer’s visit reflects a recognition that access to markets and technologies is essential to Britain’s post-Brexit recovery and broader economic resilience.

This logic mirrors developments elsewhere. Canada’s recalibration of its electric vehicle trade policy, Germany’s decision to open portions of its EV subsidy program to Chinese manufacturers, and France’s ongoing engagement all point to the same strategic calculation. Middle powers are not pivoting toward China ideologically. They are diversifying their options, hedging against shocks, and maintaining channels for engagement in a volatile and fragmented international order.

What we are witnessing is not a geopolitical pivot, but a diplomatic rebalancing driven by necessity rather than ideology.

For Britain, engagement is less about China itself than about preserving autonomy and flexibility. In a world where unilateral policies are increasingly common, multilateral approaches offer middle powers a degree of insulation and room to maneuver. Strategic partnerships are being defined not by loyalty tests, but by practical assessments of risk, opportunity, and resilience.

Starmer’s trip helps explain why European leaders appear to be “lining up” for visits to Beijing: the recognition that dialogue cannot be postponed. On global challenges such as climate change, public health, financial stability, and emerging technologies, disengagement carries costs that small and mid-sized economies can no longer afford. Engagement becomes a tool of prudence, rather than preference.

Ultimately, the Prime Minister’s visit signals a broader recalibration in Western foreign policy. As unilateral impulses intensify and strategic certainty diminishes, multilateral engagement emerges as a form of survival. In this context, Starmer’s China trip is not about choosing sides; it is about securing flexibility, safeguarding economic opportunity, and managing uncertainty. In a fractured world, the ability to keep multiple channels open may be the most reliable strategy a country can pursue.